By Foundling Friend Celia McGee

Junior Edition: New Books for Younger Readers, #13

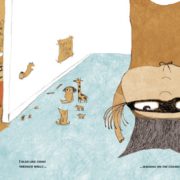

My Teacher Is a Monster! (No, I Am Not.)

by Peter Brown (Little, Brown Books for Young Readers)

Ages 5-8

Monsters are in the eye of the beholder. So are teachers. Young children apprehensive about school can’t help but conflate the two. Caldecott Honor recipient Peter Brown senses how nervous young children can be about leaving home, how accustomed they are to parents helping them through daytime setbacks and nighttime fears, how much closer they feel to their teddy bears or security blankets than they can ever imagine being to a random authority figure. My Teacher Is a Monster! (No I Am Not.) conveys with comforting humor how some newbie school-goers see only what their qualms let them, and it scares the brand-new sneakers off them. Brown takes those haunting distortions and runs with them, to the point that little readers will chortle at how silly misconceptions can be.

The absolute emotional nadir is represented by the classroom of Ms. Monster—sorry, Ms. Kirby. Her student Bobby, his hair sticking up stylishly in front–though the real gel seems terror—is not a fan. Her face is green, her bottom teeth fangs, her hands claws, her scowl permanent, her stiff brown hairdo matches her ugly outfits, and she roars as loudly as she is tall. To be fair to Ms. Kirby—but why would one be?—her admonishment of Bobby has to do with his launching a paper airplane that, by accident or not, lands at the very tips of her high-heeled shoes. Forget recess.

Such situations are hard on children who, like Bobby, can’t sit still at their desks, and hate being indoors, especially on a nice day. Tons of medical terms exist for these feelings and conditions, including being a young boy. It’s plain to Bobby, though. Nothing is as liberating and calming as chilling outdoors in the park, “trying to forget his teacher problems.”

But problems, particularly internal ones, tend to stay stubbornly rooted in the area near where nightmares sprout. Brown makes every rock, tree, plant, blade of grass and evergreen shoot seem to rise up in horror at a sight suddenly looming before Bobby’s eyes: Ms. Kirby, on his favorite park bench. Yet is there something different about her? Maybe it’s that her pretty hat with a pink flower, snatched away by a wind gust, allows a quick-sprinting Bobby come to her rescue. Teacher and pupil, friend and friend, laugh and have fun together, and together propel a paper airplane from the park’s highest spot. Ms. Kirby is transformed, crossing the line into pretty and joyful. Bobby doesn’t know if this same person will show up in class. It depends on how he’ll look at her, on how he feels about himself.

The Zero Degree Zombie Zone

by Patrik Henry Bass, illustrated by Jerry Craft (Scholastic Press)

Ages 7-10

As far as the meandering undead go, this is just a hypothesis: in Patrik Henry Bass’s hilarious, discerning The Zero Degree Zombie Zone, Bakari Katari Johnson probably feels a lot like a zombie. He might as well be dead to those around him. His classmates shun him. His teacher almost destroys him (though her intentions are good). His only friend is over-size, lumpy Wardell (who has no other choices, either). He seems condemned to eternal unhappiness. And he wears big, thick, Urkel glasses that make him look like a creature risen from opticians’ hell.

But Bass, the highly respected editorial projects director of Essence magazine, has some tricks up Bakari’s sleeve (or more precisely, in a pocket), and the bullying popular kids at the cleverly named Thurgood Cleavon Wilson Elementary might want to take heed. The most powerful leaders of the pack are the slick and athletic Tariq Thomas and his fierce, cute, trash-talking cousin Keisha Owens, the baddest of them all. And so it goes, with the ka-boom-boom-boom speed of a video game, and Bass’s mega-wit.

Historians and sociologists have located the original belief in zombies in Haiti. But those evil eaters have nothing on the army of towering, blue, milky-eyed, made-of ice zombies and their leader, Zenon the genie, summoned up by Bakari, of all kids, potentially with a marble his grandfather left him, along with both the blessing and warning that it contains magical powers and the protection of family pride everlasting.

Genies are not always as smart as they think they are. Zenon could care less about the marble and its meaning—he’s instead obsessed with the notion that Bakari is in possession a ring made of ice that is key to Zenon’s plans for world domination. It’s nothing to him that Bakari feels “a stab of pain” in his heart when he thinks he’s lost Wardell to the bad guys. (Not the zombies–Tariq and Keisha).

But bravery is bred by self-confidence, as Bakari gleans from the cousins’ knockout success in helping him fend off a zombie cafeteria invasion. It rubs off on him. With four heads better than one, the former enemies devise a plan so ingenious it might just rout Zenon for good. Alongside the idea of unexpected friendships, this is among the book’s highpoints, as are the fast moving, instantaneously communicative and spot-on illustrations by Jerry Craft, the creator, for one thing, of the immortal comic strip Mama’z Boyz.

Bass’s story makes clear that trust, loyalty, working together, and solving issues peacefully are mighty fine goals. When a person changes, it changes others, too. How Bakari and his pals—and any future drop-ins with cosmic powers—will evolve is anyone’s guess. But not for long. Bass, now a proven kids’ books talent, is following up with a series.

Cat in the City

by Julie Salamon, illustrated by Jill Weber (Dial Books for Younger Readers)

Ages 8-12

First there was Jenny Linsky. Indeed:Happy Birthday to Esther Averill’s classic book series, which got its start exactly 70 years ago with her stories of the gentle, plucky Greenwich Village cat in the jaunty red scarf, happily reissued by New York Review Books. Now, greet with pleasure Cat in the City, proof that traditional opposites can attract and actually roll around in teachable moments.

As Julie Salamon sagely intimates and Jill Weber reflects in her blithely New York-centric, colorfully bittersweet illustrations, there isn’t just one way of perceiving the city, its famous buildings and architectural landmarks. To a cruising hawk, bustling Washington Square down below is merely a “rectangular field” for hunting. What initially looks like a “wrung out mop” to the predator comes into focus as a tasty-looking feline. He swoops, he misses, and the tangle of fur skedaddles instead smack into Roxie, Henry, and Maggie, each a dog with a distinct personality and a hostile, sarcastic attitude toward anything that purrs. Yet the dogs’ hearts inevitably melt at so pitiful a sight. Marched briskly off to Roxie’s human’s home and tschoke shop, Pink Patti’s, he’s washed and scrubbed, blow-dried and fluffed up, and Patti names him “Pretty Boy.” The effects of kindness, taking risks on strangers, raising up the underdog (or undercat), and exchanging truculent “self-reliance” for the warm pleasures of community add special value to seemingly everyday adventures.

Since the narrative favors the animal’s eye view—dearly beloved by the many children who stand just about as tall–Weber often cuts scenes with humans off at the waist, and Pretty Boy’s unscripted trip to Maine in a Manhattan family’s car trunk is all the scarier for his being stuffed in amongst sunhats, tennis racquets and boat bags that dwarf him. Vacations, though, remain escapes from real life–back home, Patti has been priced out of New York. The solitude would have pleased Pretty Boy once; now, not so much.

Salamon fills the void in this particular one of Pretty Boy’s nine lives with the friendship of the family’s young son, Eli, who himself dreads the mean-spirited isolation of a new school, and wants, in an unmusical family, to be a musician. Operating under the novel’s philosophical stance that happiness is helping people, and animals, out of tough spots, Pretty Boy—and Salamon—can give surprises as well as they can get. Pretty Boy introduces Eli to the “Cello Man” who regularly plays in Washington Square. Hold onto the name of another New York institution, the Barrow Street School of Music. Weber draws it to scaled-down perfection. You just never know.

Circle of Stones

by Catherine Fisher (Dial Books)

Ages 12 and up

“How do you know how a lost soul feels?” a Druid king asks in Catherine Fisher’s Circle of Stones. And how do you know when it’s healed? The first question and the second, almost as ineffable, resonate in Fisher’s circumnavigation of time and magic, the modern day, the ancient past, and history not so distant. Toying with alternative realities and dimensions, she fashions a chain of interlocking stories that at first seem as unrelated as can be. She’s also the Young People’s Laureate of Wales, a title roundly deserved for resplendently re-configuring the fantasy-novel category, but also with an aura of the mythical.

A circle can be many things—endless, sacred, enfolding, imprisoning, concentric. It also shapes “the ring of years,” as Fisher writes, and characterizes even the pox pustules that cause the wise and good Druid king’s banishment, and plague one era after the next. Is someone sinned against or sinner? Such tortured wonderings are as well cruelly circular in Fisher’s tripartite division of history, bound together by often the most mundane room, incident or passing relationship, and intertwined by bewilderment, delusion and specific forms of death.

In the here and now, 17-year-old “M,” barely able to function after a mysterious childhood trauma and tabloid feeding frenzy, has been shuttled from one foster home to another, in secrecy, carefully observed by social workers and psychiatrists, and under surveillance, for some fatal cause celebre, by the police. Almost at the age of liberation from this lock-down but not from the unresolved memories that follow her (along with an ominous, darkly cloaked figure of a man), “M” comes to a stop at last with a sense of homecoming in a place wholly unfamiliar—the beautiful, “golden” city of Bath. It mesmerizes with its extraordinary circles of architecture, the hot springs below, revered by the Romans through magnificent mosaics, and dedicated to the goddess Sulis, whose name returns as “M” picks it to be hers, too. A moment’s thought, it circles Fisher back to Balud, the Druid king, then spirals forward again, to the impoverished aristocrat Zac laboring three centuries ago under the half-mad architecture genius John Forrest, who’s intent on creating in Bath the world’s first circular street, and honoring the Druids and their mysterious stone structures. What would Jane Austen think?

Sulis recognizes such layered propositions as nourishing her outer and her inner life. Twirling madly through her personal past and the histories she intuits are bound up with it, she’s confronted by the delusions she’s swaddled herself in. Among the rare ways of breaking out of a circle is to fly. But then, what are the consequences?