Foundling Family Book Review – Issue # 21

Junior Edition: New Books for Younger Readers, #14

By Foundling Friend Celia McGee

By David Ezra Stein (Candlewick Press)

Ages 5-8

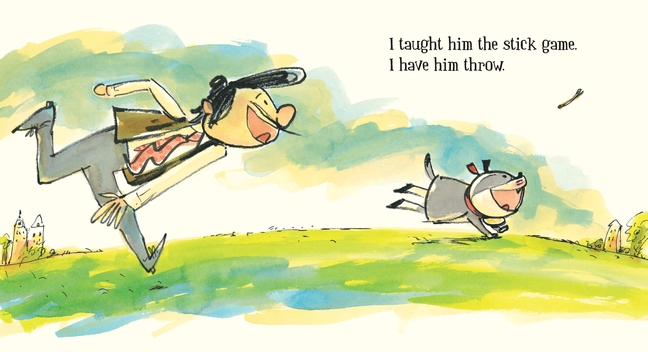

Self-delusion can be the unintended mother of invention, a concept simplified and humorized in David Ezra Stein’s (another of the Caldecott chosen) I Am My Own Dog for the youngest of readers and those who tuck them in at night after reading them a good book. It’s also a story with which most child pet-owners can identify. Yet the canine star of Stein’s book is a mutt without an owner—“I’m my own dog. Nobody owns me. I own myself.” That’s all very well for leaning suavely against fire hydrants while tamer pooches namby-pamby by, some even carried in purses. Such a pampered existence is not for him. He’s a hard-working dog (“I work like a dog,” as he might not know the saying goes in the world he refuses to join), he puts himself nightly to bed (after fetching his own slippers), and his nighttime sleep habits are, he believes, solely of his devising. How could there be such external pressures as physical discomfort? He prides himself on reacting badly to hypothetical situations involving interacting with humans in activities he thinks he enjoys more on his own.

But Stein hints at an inkling of self–doubt in a canine who has to look at himself in the mirror every morning and chant “Good dog. I am a good dog” to psyche himself up for his one-dog independence. It has never occurred to him that there are circumstances where humans are actually desperately needed, like having his back scratched in a place he can’t reach. In contrast to the self-congratulatory self-satisfaction Stein holds up as a dubious but hidebound character trait, in the dog’s eyes tjere’s a pathetic loneliness in the back-scratcher, who follows him home. Another expression that has apparently escaped himis “you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” Good deeds sneak up slyly. The dog buys the guy a leash so he can lead him around, introduces him, he thinks, to squirrel-chasing and stick-throwing and sitting on command even though they appear of his budding friend’s own experience and volition. It’s a pleasantly dirty mess to clean up after humans with dripping ice cream cones, but someone has to do it. And someone has to admit to a pleasantly changing dynamic in life. This should ring a bell, or maybe elicit the satisfied sighs of friends snuggling up together, that, if carefully listened to, could last a lifetime. Relationships are not built in a day, and often it takes working “like a dog all day” to get there. But the emotional payoff is worth it.

By Kate DiCamillo, illustrated by Chris Van Dusen (Candlewick Press)

Ages 6-9

Kate DiCamillo provides several tip-offs that, in her rootin’-tootin’ Leroy Ninker Saddles Up, her daffy, soulful and surprisingly spunky squirt of a protagonist lives somewhere you can’t just up and travel to, and that’s the past. Lerpy works the concession stand at a drive-in movie theater. The family cars parked there would be vintage today. Moreover, though a grownup, he says “Yippie-i-oh” a lot, which you don’t hear much anymore. (In her trademark zippy way, Newbery medalist DiCamilo also coins some droll, cheerful, innocent-sounding expressions exclusive to Leroy that come in handy for letting him largely suppress the scarily different person he used to be, with a past of his own to hide.) Quaintest of all, he dreams of owning Western boots, a twirling lasso, and a ten-gallon hat: he wants to be a cowboy. That’s a pretty tall order for a product of a reasonably urbanized landscape (Leroy lives in an apartment). That he wants to be “never ever afraid,” like the Marlboro men he worships on screen says more about Leroy than them.

After all, there’s little purpose to exciting dreams and aspirations unless they’re acted upon. Sometimes friends have to prod a dreamer from fantasy into reality. For Leroy, that impetus comes from his co-worker Beatrice Leapaleoni, who gets to the heart of what every wannabe cowboy needs to become the genuine article. Like Leroy, who owes his ski jump of a nose, protruding ears, gap-toothed grin and eyes resembling surprised donut holes to illustrator Chris Van Dusen’s graphic sense of humor and giddy-up pace, Beatrice, and the rest of the book’s characters, sport equally goofy yet endearing features, but she also has common sense: Leroy needs a horse.

With a determination that should teach young readers a thing or two, Leroy scours newspaper ads for that very thing, and once he finds it, provides such pointers as repeating the printed address twice, safekeeping it in his pocket, and grabbing “fate” by the tail. Her name is Maybelline, a stubborn old steed that, like most animal versions of humanity, has her quirks—1) she responds only to compliments 2) has a prodigious appetite, and 3) hates to be alone. The first makes a poet out of Leroy, the second a short-order cook of masses of spaghetti, and the third presents the conundrum of how to fit Maybelline into Leroy’s apartment so she doesn’t have to be alone–which he can’t. The solutions he arrives at, and how adaptability and growing mutual affection bring the pair even more friends– including the African-American siblings Maybelline bonds with when she briefly runs away–are funny and endearing, while also opening the shy floodgates enabling Leroy to confess his past sins to the understanding Maybelline. He’s a good way toward his goal of matching his idealized cowboys. It’s a catharsis on the order of the epics he and Maybelline watch, together, on the drive-in movie’s screen. Maybelline, notably, is partial to love stories, a romantic tendency not out of character for a horse that shares a name with a popular cosmetics line. But stasis can hardly set in for these two—Leroy Saddles Up is only the first in a new Katie DiCamillo series.

By Joanne Rocklin (Amulet Books/Abrams)

Ages 8-12

Fleabrain, the miniscule insect in shining armor who hops in to save the day for an exceptional young girl named Franny Katzenback , is anything but. Joann Rocklin, the best-selling author of this new book is no slouch, either, and she tops herself here. Joining the latest mini-trend of writing young people’s fiction inspired by, in dialogue with, or subtly referencing classic books and their authors, she ostensibly sets up an amusing tale about Fleabrain’s jealousy of Franny’s passion for the newly published Charlotte’s Web, an instant classic and, in Franny’s well-read estimation, “the greatest children’s book of all time.”

Fleabrain Loves Franny gives Charlotte a run for it’s curly pink tail. The reasons Fleabrain loves Franny may be too numerous for even one of his intellectual role models, Pascal, to untangle and enumerate, but in fairness, some of these rationales border on self-serving tactics in Fleabrain’s battle to change Franny’s admiration for a silly spider in a children’s book into true love for a real-life flea who’s learned, romantic, brave, resourceful, a multilingual polymath, admittedly a little smug, but a doting presence close at hand, at the tip of the family dog’s tail.

It’s 1952, and Franny is recovering from polio, first in an iron lung and now her confined to a wheelchair. Rochlin piercingly portrays the plight of a studious girl steeped thoroughly in an understanding of the very affliction she’s suffering.

Given a wide and superstitious berth by all she encounters, only her family keeps her company, along a mean nurse to put her through the daily torture of exercises intended to get her legs moving again. In the Katzenbacks’ affluent Jewish neighborhood in Pittsburgh also live the famous and reclusive Dr. Jonas Salk, working on a polio cure, and his associate, Herr Gutman, whom Franny only knows as a an occasional, quiet dinner guest, the great sorrow in his eyes for the wife and daughter lost to the concentration camps. McCarthyism’s specter also hovers, ready to strike.

Thanks to magnifying bottle top from a “Sparky’s Finest”s soda, Franny is finally able to see Fleabrain. Magically—a word not used lightly—he restores friendship to her. Most obviously in common is their love of books. (Somewhat ominously, Fleabrain announces he’s “consumed” almost every book in the Katzenback’s extensive library, and Franny ultimately figures out that the notes, love letters, poems and literary exegeses he leaves her are written in blood.) Rocklin’s knowledge of the science of nuclei and other invisible but living organisms is prodigious. But that’s merely hardcore erudition. Transferring to a tail hair of Lightning, a sweet elderly horse harboring romantic secrets, Fleabrain teaches Franny to ride, then fly, as if on a mystical sky steed out of Chagall, performing miracles and mitzvahs, saving lives and committing noble acts of daring.

These also represent the sad, sardonic Franny embracing belief—in the miraculous, in human nature, in love, and perhaps a higher being. Anger is disowned, faith accepted, and the future faced. For Rocklin there is such a thing as being born again, and with that to change the world. As for one small creature, a job is complete, a literary prejudice overcome, if not a love requited. To borrow from Charlotte’s Web, which Rocklin does:Some Flea.

By Carl Hiaasen (Alfred A. Knopf/Random House Children’s Books)

Ages 12 and up

There’s scads of territory where fans of Carl Hiaasen’s gonzo detective fiction might expect to find his occasional character Skink (given name Clint Tyree)—college football star, crusading ex-governor of Florida downed by corruption, eccentric, bibliophile, as odd in attire and demeanor as in huger-than-life personality, nature lover in a shower cap with a fine collection of artificial eyes he pops in and out of an empty socket, funny as a dancing alligator in the disappearing swamps he holds dear, old in years, crazy young in spirit, and smart as all get-out. But they may not have guessed in a book for young readers.

Yet that’s just what Skink—No Surrender is. It’s Hiaasen’s first, and a yarn for our times. He hooks up with—or rather hooks, with his undefeatable and frenziedly brilliant know-how—a teenager, Richard (who narrates the story but adolescent-like, divulges not last name) a beach-combing, alienated kid still mourning his father’s death, close to no one (certainly not his Mountain Dew guzzling stepfather) except his cousin Malley, who’s even more bored by their suburban background than he is, and more rebellious. She’s the type to suddenly disappear, this time ostensibly to get out of being shipped off to boarding school, but more likely kidnapped by a weasly character she met in an online chat room.

That’s the Internet as a tricky, villainous fact of modern life, but so are the cell phones through which Richard and Malley are finally able to communicate, Malley conveying clues that only Richard understands, which point to a hiding place way up the Panhandle on a decrepit houseboat, Malley handcuffed by the “creep” she first thought was a cool DJ. “Will the bride be wearing handcuffs,” is one of Skink’s lines.

It doesn’t help Richard and Skink’s in the subsequent pursuit of the bad guy that dead people turn out to be alive, and living ones, dead. A funny off-shoot is the temporarily crippled Skink, who eats mostly road kill but was trying to save a baby skunk off the highway, teaching Richard to drive, propped on one of his thicker books, Steinbeck’s East of Eden. It’s known that many oddballs populate the social fringes of Florida culture—and, with that, Hiaasen’s fiction. Skink—No Surrender turns one of his grandest nonconformists into a boy’s dream companion—and Richard learns to wake Skink from his moaning nightmares of Vietnam. Thoreau knocks on our memories, but also Hunter S. Thompson.

In Skink—No Surrender it takes a dozens of cops to mess up royally, and a one-eyed outcast and his creator to perceive goodness, generosity, growing up and an alert peace of mind deep down and far ahead. Wherever there’s an open road and a mystery to be solved, Hiaasen’s high opinions of freedom and orneriness are on it. He doesn’t speak down to his new audience, and he also doesn’t sugar coat the America in which they’re coming of age. The future is for the young to figure out. Only some are lucky enough to run into a guiding light who has lasted long enough to help them.