Foundling Family Book Review – Issue #16

By Foundling Friend Celia McGee

The Day I Lost My Superpowers

By Michael Escoffier. Illustrated by Kris Di Giacomo (Enchanted Lion Books)

Ages 5-8

Quite a few children may doubt that they have super powers—very sure instead that these belong to the imaginary monsters in the dark, the big bad wolves stalking through fairy tales, the giant robots that stomp through nightmares, or the sheer terror of the unknown lurking around every street corner.

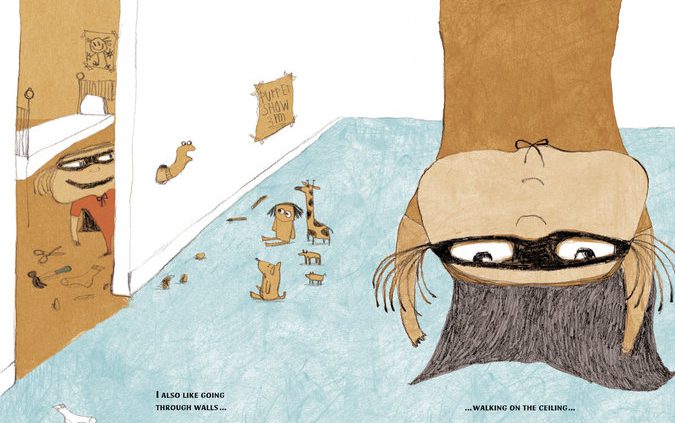

Not so the wildly charming, dashingly masked and caped, winsomely funny-looking little girl (though we wouldn’t want her tailor) sent forth on her daily crusades by Michael Escoffier and Kris Di Giacomo to demonstrate her magical energies. This book makes loving fun of its subject while showing her confident self-image, her unshakeable and endless sense of fancy, and her encounters with surprise Super Powers at the same time.

Readers will be tickled and touched by the wispy-haired super-heroine’s deadpan delivery, her utter conviction that what she says is comfortingly believable not only to herself but to her audience. Humor is added by the gently contradictory, reality-revealing character of Kris Di Giacomo’s drawings.

Try flying, for example, which mini-Super does with great success–thrown up in the air by her father, she truly feels she’s airborne because she knows she can count on landing in her daddy’s arms. Not that their aren’t skeptics, her toys among them, as they see her practice flying on her own off the end of her wrought-iron bed, and fall flat on her face.

Super Miss’s versions of “making things disappear,” communicating with animals, and, “superhuman,” breathing underwater are hilarious, and, when it’s time to pull the trick of going “back in time” (more formally known as regression), draping herself sleepily, pacifier and all, over her mother’s shoulder, it’s heartwarming.

The Lion Who Stole My Arm

By Nicola Davies, illustrated by Annabel Wright (Candlewick Press)

Ages 8-10

A lion who is very different from (the grammatically correct) a lion that. For Nicola Davies that distinction matters a lot, since she applies it to her story of Pedru, a lively young boy in the village of Madune, in Mozambique, who loses his right arm to a lion when he gets separated from some fishing buddies.

From then on, he refers to the lion as having “stolen” his arm, as if he could retrieve it, along with his dignity, self-confidence, spear-throwing capabilities, and the company of his friends, who shun him, leaving him to brood and fear that “I won’t be myself anymore.” The lion, on the other hand, becomes human to him.

Pedru’s obsessing about the lion, Davies implies, makes him see it as “his” lion, transforming it into his ultimate opponent, the intractable enemy, the evil that must be wiped from the face of the earth where the villagers till their crops and raise their squealing bush pigs. Not only there but in Pedru’s dreams are its hunting grounds.

Revenge can be a potent motivation and anger a weapon. Relentlessly perfecting his spear-throwing with the strong arm left to him, one day Pedru manages to kill a lioness wearing , of all things, a collar, which bears the words ”Return to the Lion Research Center at Madune.”

Words do matter. Thanks to the electronic collar, Pedru is taken up by the research center, which studies lions and is working to win for them preserves in large, protected swaths of the wild. It’s there that the lesson comes across that, like Pedru, Anjani, “his” lion , is a member of a family, and the reason why he roves far and wide for food.

Davies’has Pedru grow up to work toward a Ph.D. in animal behavior, sub-category King of the Jungle, and enjoy the preserves that have come into being. But it is made clear that his own reconciliation with what happened to him has given him the intelligence and inner strength to recognize that “his” lion has given him more than he ever took from him.

Uncertain Glory

By Lea Wait (Islandport Press)

Ages 10-14

There’s new business to be built, loans coming due, employees and apprentices to train, a worthy, sought-after product to be designed, and a customer-base to be broadened. So it’s nose to the grindstone for Joe Wood of Wiscasset, Maine, in 1861. Joe, an aspiring writer, journalist and extra wage-earner for his parents, is trying to revive a printing press and publish a newspaper out of the formerly broken-down printing establishment a cousin left him.

Joe is 14. His friend and single employee, Charlie, is almost 16. Their willing and education-hungry apprentice, Owen Bascomb, is nine.

Lea Wait’s Uncertain Glory holds up their youth and their dedication to what, in our age, would be adult responsibilities, as an admirable matter of fact, eliciting a continual fascination with how different these young people are from those the same age in our time and with its temperament.

The same goes for the distinctions Wait subtly portrays between contemporary means of communication and news dissemination and those of a century and a half ago. Gathering on the horizon is the gunfire at Fort Sumter and the outbreak of a full-scale civil war. Joe is determined to chronicle these and every wartime development with as much immediacy as the telegraph system and his own on-the-ground reporting can achieve. The additional printing jobs that Wait has come his way—bills to be voted on by the State legislature, copies of The Act to Raise Volunteers, advertising cards for studio photographers suddenly in demand for departing sweethearts, soldiers’ identification cards—tell the story of the war’s beginning, and the innocence and enthusiasm with which men marched off to a deadly, dehumanizing, and prolonged civil conflict. Chapters are interspersed with mockups of The Wiscasset Heralds front pages, visual accompaniments to the nearing drumbeats of war.

New arrivals—Nell Gramercy, a beautiful, afflicted and mystery-laden spiritualist (she’s 12) being shopped around town for séances by her controlling uncle and aunt—also give him plenty to record and contemplate. Nell is wise beyond her years as well as her profession, which helped lay the groundwork for early American psychiatry. Her clients, she tells Joe, seek her out “to free themselves from guilt and sadness.” She averts a tragedy, too.

Owen’s burden, borne with dignity, grace, and courage in the face of bullying and worse, is that he is African-American, born into and largely at home in the small northeastern harbor town that has included his family for generations. Their presence is taken for granted among the many large and small social distinctions that mark the town. That these will change, rankle and come to nasty, heated arguments and physical blows among adults as well as their children is augured and confirmed by Owen’s teasing and beating at the hands of a white gang when he announces that his father will be the first to sign up. “Real men are white” is their shrill retort. ’s enlistment is likewise rejected. This is a novel where the intervening centuries slip away, leaving prescience and promise with the overwhelming demands of now.

Plus One

By Elizabeth Fama (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

Ages 12-17

The conventional contrasts between light and dark, black and white—with pale or bright usually getting the better part of the deal–have forever oozed religious arrogance, warfare, fear, prejudice, and oppression, and colored the Manichean division of evil and good. Yet award-winning favorite Elizabeth Fama has been able to conceive an unforeseen way to think about the divide between daytime and night, taking a great leap into an alternative reality that is nevertheless fed by events that really happened. The uncanny America she constructs is an hypothesized present where the population has been separated into so-called Rays and Smudges.. Rays live by day, Smudges by night. In a resonant demographic development, Smudges have started to outnumber Rays.

Plus One’s Sol (short for Soleil) Le Coeur, a disaffected teenage Smudge, has had the same explanation for her inferior nocturnal separateness drummed into her in school, by television, and through the answers she’s expected to “regurgitate” on exams. “In the fall of 1918,” as she tells it, President Woodrow Wilson set up a Federal Medical Administration that eventually divided all medical personnel into day and night shifts, a model of efficiency soon imposed on the entire country, together with an “Office of Assignment to make decisions about who would be Day and who would be Night. The Committee on Public Information helped people to accept and understand the change.” In other words, there are lethal enforcers known as Night Guards, and a secret procedure detrimental to Smudges . Among her earliest, most desperate feats—reminiscent of Czarist Russia, where young men and boys cut off fingers or toes to avoid military conscription—Sol deliberately mutilates her right hand in order to be rushed to a hospital where she has a special mission to accomplish for her dying grandfather—and despite terrorism hiding in plain daylight.. A young doctor she meets and falls in love with in the process has been interwoven in her life far longer than she realized, and is much less of a pureblood Ray than she had assumed.

Only a few are brave in this new world, and their courage is something they have to perceive in themselves.