Foundling Family Book Review – Issue #14

By Foundling Friend Celia McGee

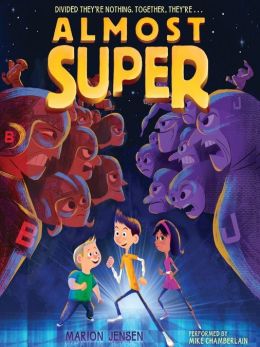

Almost Super

by Marion Jensen (Harper)

AGES 8-12

Leap years—when April hangs a 29th day on its rear–have a few, frankly corny, traditions attached. Among the rich and famous, Ja Rule has a Leap Year birthday. So did Lord Byron

But it has a whole different meaning for the Bailey and Johnson families of Split Rock, an ordinary town in Middle America, where every April 29, those over 12 (in real years) in both families are granted superpowers. The zany result is that they also have to try very hard to blend in with their non-super-powered neighbors. One way appears to be with dorkiness (unless that’s not intentional), and with dorky names like Verna or Rodney or Rafter (that’s the first name of the teenage Bailey who narrates this tale, and what kind of name is that, anyway?). “Technically,” Rafter’s grandfather says, “we’re a bunch of freaks.”

The problem is that the Baileys and Johnsons are sworn enemies—the Baileys proud they’re the super heroes, and the Johnsons the super villains. They fight all the time (Rafter has begun to notice that Johnsons always show up in tea, which he suspects is a slick move). Some can fly, some are shape-shifters, others shoot fire or water out of their fingertips, others are just plain super-smart (this comes in handy in this Internet, computer science, and hacking age). Rafter is particularly scared of Juanita Johnson, who goes to his school, has been sending him dirty looks even before they get their superpowers, and, truth be told, strikes Rafter at inopportune moments as rather pretty. They are both about to learn that there are some qualities in life even better than super powers, and that super powers are, in fact, pretty useless without them.

Dawns April 29, with Rafter, his younger brother, Benny, and, doubtless, Juanita waiting with bated, about to be super-powered breath. But something goes terribly wrong. Their super power gifts are duds. Benny can turn his belly button from an innie to an outie and back again. Rafter can light polyester on fire with the touch of a hand. While Juanita—dud gift, too, and it has to do with spitting. As the three huddle drearily in their duddliness, they become close. To their shock, they learn each family thinks it’s the super heroes, and the other, the super villains. That leaves the dud-scarred threesome with the realization that maybe people, super-powered or not, are meant to get along. And that super powers make you feel better if you use them for good rather battling. Juanita has an uncle,for instance, who, though not of the super ilk, is a painter, and uses his art like a super power to bring out an inner truth in his sitters (his portrait of Juanita is lovely indeed).

Thankfully, these three super-duds have not been robbed of their quick minds—put three heads together and their emerges a notably superior intelligence—or of the sense that something weird is happening in Split Rock. All three glimpsed unprecedented flashes of light, for example, just before they got their non-super powers. Might someone just have been practicing on them before getting around to the destroying the fully super-powered? With courageous snooping, they encounter some sinister super-whackos bent on just that. Rafter, Benny and Juanita have to get to this scary scoundrel before he gets to the other Baileys and Johnsons.

They’re resourceful, especially when acting as one, and once their families find out about the dastardly fellow—October Jones by name, and the leader of a super criminal clan—they not only strike a permanent truce, but consolidate to hunt down October and his gang before the bad guys get ideas about Baileys and Johnsons in other towns.

Super hero or not, anyone can look into that future and figure there will be a sequel.

The Ghost of the Mary Celeste

by Valerie Martin (Doubleday/Nan.A.Talese)

AGES 14 AND UP, AND ADULTS

Hannah Briggs is 13 when the spirits of the dead start manifesting themselves to her, speaking of their loved ones, their passions and hopes for them—some rather creepy. It’s 1872 and the height of the 19th-centry Spiritualist movement. Hannah’s particular spirit visitor is her sister Sarah, who disappeared, under unknown circumstances, along with her young daughter and husband, off the merchant ship the Mary Celeste, which her husband captained. Nor was the crew anywhere to be found when the vessel was sighted, adrift and bereft of any human presence, in the waters off the Azores. It was towed o Gibraltar, to much rumor and speculation. Mutiny? Pirates?

In the enthralling novel that Valerie Martin has conjured from this notorious piece of maritime history, we are made witness to what could have happened to the ship instead–horrifying, pitiless, inescapably violent, and beyond control of man. History is never just history. It’s a shifting, variable, subjective record of things past. Martin has extensive knowledge of how this lends itself to perhaps our favorite form of literary expression, fiction–which The Ghost of the Mary Celeste is also about.

Hannah and generations of her seafaring Massachusetts family have lost many to the sea. So many that there is talk of a family “curse.” It is just such losses—traumatizing to those left behind and inexorably longing for the dead’s every familiar touch—that, not so many years after the Mary Celeste incident, sends hundreds flocking to see the famed and beautiful spirit medium and public speaker Violet Petra. They seek her out in private séances to help them communicate with and gain solace from their dear departed. For Violet’s message is this: take joy in the fact that the spirits are among us at all times, for the human and the supernatural world are as one. Spirits are here to announce, through Violet in her trances, that they are waiting patiently and tenderly for us to join them in their transcendently harmonious, picturesque and eternally spring-like beyond.

Violet, then, is all the fashion, taken up by wealthy families whose sadness she has lifted, traveling in style, gracing the attractive campgrounds and vacation communities that have sprung up for the Spiritualist faithful, and mesmerizing all with her strange eyes and flowing hair. But she’s also under the scrutiny of the young female reporter Phoebe Grant, who is determined to prove that, like all so-called mediums, Violet is a fake. What she does find out is that Violet suffers from her own heartbreaks, her own cruelly brief love affair, and the growing fear that her powers are diminishing, her glories along with them. She and Phoebe become friendly, and one day, just by chance—or is it?—she thrusts into her hands the issue of Cornhill, the English magazine, with a version of the story of the Mary Celeste written under a pseudonym by a then unknown Conan Doyle. Doyle really did write and publish such a story, which helped start his career, and he threads through Martin’s novel, under often fictional circumstances, but with his factual racism stupendously intact and only momentarily shaken when he ends up making the acquaintance of an African-American intellectual and civil rights pioneer (also based on an historical figure). Throw in William James and the American Society for Psychical Research, the religious and historical forces that erupted at the height of the, Spiritualist fervor, and, in Martin’s hands, the blend becomes half-shrouded mystery mixed with cunning clues.

I’d also like to note that the novelist Colleen Gleason recently published her first YA novel, the captivating Clockwork Scarab (Chronicle Books), about a detective duo formed by Mina Holmes (Sherlock’s niece) and Evaline Stoker (Bram Stoker is her dad). Sir Conan Doyle would be both shocked and proud.

The Tyrant’s Daughter

by J.C. Carleson (Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers)

AGES 12 AND UP

Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria, North Korea, Ukraine—over the decades and also in recent weeks we have watched these countries and others like them, at their most unstable and vicious, scroll across our television and computer screens, kick starting our outrage at dictators, totalitarians and self-appointed royal dynasties. Some of the more sickening images involve the mind-blowingly immense, incalculably costly, invariably vulgar palaces and estates built on the backs of the citizens their rulers have impoverished and oppressed, while sending the rest of their untold millions flying off to Swiss bank accounts.

Author J.C. Carleson, a former undercover C.I.A. officer, draws on her experiences—mainly Baghdad, she writes in her Author’s Note—to open the doors on the intrigue, carelessness, frivolities, family bonds and close-bound murders that live within those mighty, well-guarded walls. There the families of the tyrants—unless displaced by coups or revolutionary eruptions —tend to remain, with few exceptions, obliviously cut off from economic and political realities, and also the ugly truths about those who may do evil but genuinely love them. Tyranny has a human face unseen by those kept innocent and ignorant by the very people who would sell out all others, wives, siblings, and trusted associates included.

Such is the world Laila thinks she has left behind when, at 15, she, her mother and her little brother (at 6 already “The Little King”) are forced to flee their unnamed Muslim country after an overthrow orchestrated by her father’s brother, who murders him in front of his wife. Now, escorted there by a shady C.I.A. agent, they live in shabby, lonely togetherness in suburban Washington, D.C. Laila’s beautiful, perfect mother tries to keep up appearances while shopping at J.C.Penney, and beginning to drink. Laila is so desperate to fit into American culture that, about to enter the local high school, she asks for an “interpreter” not of the English language (which she has been taught to speak perfectly, with a British accent) but the customs of American adolescence. She finds that in Emmy, her first sincere friend.

But, like the layers of burka, veils, scarves and formless clothing Laila’s mother used to shed in airplane bathrooms on their trips to Paris and other shopping and social meccas, Laila begins to catch disturbing incongruities. Strange mountain tribesmen from her country hold meetings with her mother in the family living room. She picks up on unsettling conversations between her mother and Darren, their C.I.A. shadow, and must face not only the atrocious facts about her father and their background but what her mother’s increasingly stealthy and cold-blooded behavior might mean. In Laila’s psychological unraveling and depression, she even suspects Ian, the cool and kind-hearted schoolmate she takes as her boyfriend. She is also forced to change her her mind about Amir, the youngest of the tribesmen, when she hears why he is really in the U.S., and listens to him describe the chemical weapons used against his village back home. Declaring herself “The Invisible Queen,” she decides to plot against the plotters—whomever they may reveal themselves to be. That’s not so easy, more like devastating. But Laila will carry on with the quality most lacking in how she was raised—as her briefly honest mother says, “love.” It’s an informed, open-hearted, lessons-learned love for individuals with a right to her affection, for for those shut out of palaces and denied freedom, everywhere. Whether the people and life choices she encounters along her path are worthy, she will now be able to be the judge.

Meeting Cezanne

by Michael Morpurgo, illustrated by Francois Place (Candlewick Press)

AGES 7-10

If Michael Morpurgo’s name rings a bell with American parents, it’s likely they know him as the author of War Horse, which started life as a book for young readers, then morphed into a play that took audiences by storm. He was also the British Children’s Laureate from 2003 to 2005.

That he has a profound understanding of troubled boys War Horse showed us, and Meeting Cezanne, though a far gentler, slimmer, more sunny book, has some of that element. The sunny part especially comes through in the alluring illustrations by Francois Place, Morpurgo’s frequent collaborator, which evoke the 60s of the book’s time period and sharing the glories and details of Provence.

It’s hard for a youngster to part from a parent, and Yannick really doesn’t get why he must leaves the mother he loves dearly–there seems not to be a father in the picture of their Parisian existence—to stay with relatives in distant Provence when she has to have an unspecified operation and spend a month in bed. Will they all be like his “big and bustling” Aunt Mathilde, who visits from the south on occasion and irritatingly smothers Yannick with hugs and kisses, and pinches his cheek, way to hard. His mother tries to convince him with stories of his Uncle Bruno’s convivial inn, and shows him a book of Cezanne paintings of the countryside near Aunt Mathilde’s house, “and he loved it there,” she says, “and he’s the greatest painter in the world.”

Good to her word, Provence is beautiful and Yannick is picked up in a Deux Chevaux, no less, though his gorgeous, older cousin Amandine is snooty and rude, and he is expected to pitch in like the rest of the family working at the inn. Uncle Bruno takes a fatherly pity on the lonely Yannick, and starts teaching him cookery’s craft. Little does Bruno know that, despite this new education, he’s about to commit a terrible crime when the inn’s “best customer” comes to dine and leaves a doodle in one corner of the paper tablecloth. After dinner, Yannick discards the table cover with all the others, not realizing that this honored guest always leaves a little drawing for Uncle Bruno like this–treasured because “he’s the most famous painter in the world.” Soldiers don’t have a premium on courage, and young Yannick seeks out the great man, identifiable throughout by his striped cotton sweater. He apologizes, and gets a drawing from him (along with another father figure?) in return. But there’s something about that striped sweater…. Hiking back proudly to the inn with his drawing, everyone is impressed that he’s been befriended by…Picasso, Cezanne’s artistic heir. That earns Bruno respect all around—and a heavenly kiss from Amandine. As for his meeting the great artists, “They’re both wonderful, and I’ve met both of them—if you see what I’m saying.” For his part, Yannick feels called to become a writer. If you see what I’m saying.